Janek Simon’s many exotic trips over the past dozen years have served to develop his para-artistic endeavors, vested on the fringes of economics, art and post-colonial thought. As goods subject to his turnover and re-export he included even the products of national culture (“Year of Polish Culture in Madagascar”, 2006; “Nollywood Ashes and Diamonds”, started in 2014). The exhibition “People with the Heads of Dogs” is an offshoot of these earlier experiences, as it also inverts the perspective of the artist as observer. Simon’s main topic of interest shifts from intercultural exchange towards the subjective observations of a researcher-traveler: exploration, and confabulation, too, of which the experiences of recognized travelers, reporters and artists are full of.

The exhibition features two main protagonists. The first is a man who goes by the pseudonym Seven, a Hindu man encountered by Simon in India during a workshop in Auroville. The fruit of this acquaintance is a video recording of Seven’s as he animatedly recounts the impossible twists and turns of his unusual life story: intimate relations with the English Queen, murdering Olof Palme, co-directing Hitchcock’s “The Birds”, along with other infamous stories from the previous century, which he whole-heartedly claims to have had a part in. Seven became a source of inspiration for the artist as he began to incorporate autobiographical themes in his work, together with analyses of how much fantasy can be inscribed into the process of relaying and absorbing information, in creating one’s identity and self-creation.

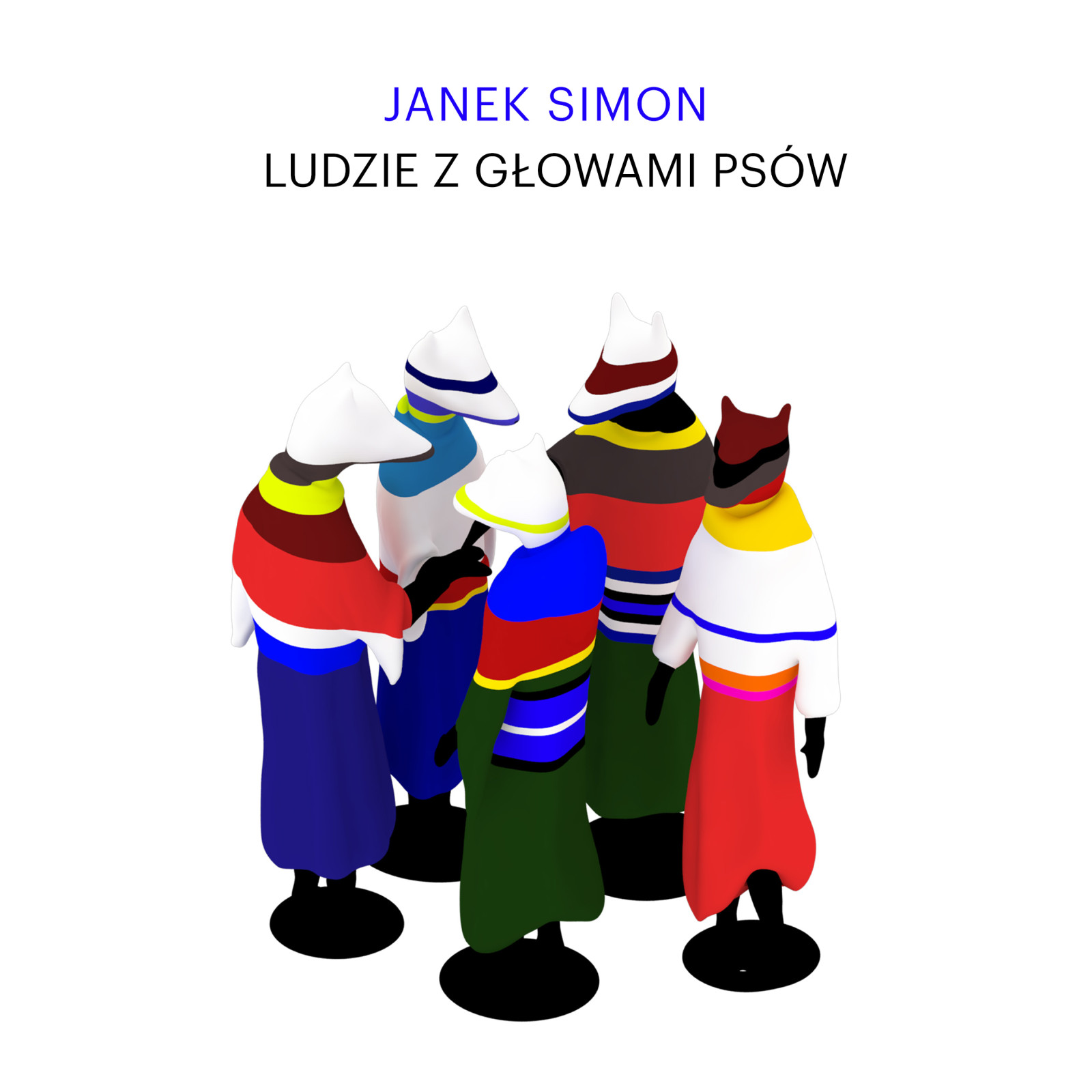

The exhibition’s second main protagonist is the artist himself, Janek Simon. The props and artifacts he collected are a meandering, sentimental collection. They include objects that hold significance for the artist and his history, both in personal and professional terms. This collection is shown along with the dog-headed people of the title – 3D-printed sculptures inspired by the medieval illustration accompanying the writings of Marco Polo, who described the country, which he claimed existed in Andaman Islands, of mythical creatures known as Cynocephali – beasts that had also been described in earlier centuries by the likes of Pliny the Elder.

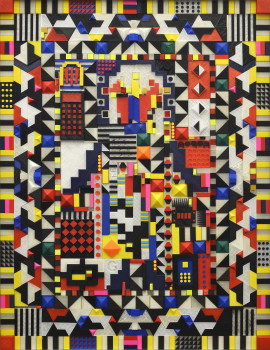

The same technique and material was used to stitch together a personal narrative of Simon’s emotional and artistic life, made in the form of a relief based on the ornamental tapestries of Afghanistan, the Caucasus, Poland’s Podlasie region and of West Africa. The artist, with his characteristic fascination with interlinked, anecdotal stories, relays his own story using a particular visual code. At the same time, he creates one more autobiographical loop in referring to his very well-known first work, titled “Carpet Invaders”.

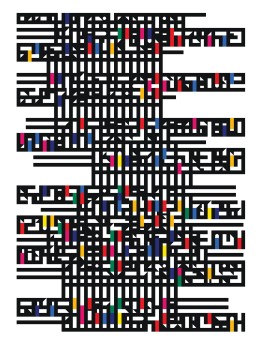

The exhibition has its lyrical finish in the form of poems coded within Simon’s abstract artistic compositions, written in response to emotions spurred by the collapse of subsequent intimate relationships. For the first time, his interest in economic, statistical and technological systems has been decidedly turned inwards, toward the artist himself. It turns out to be a characteristic, critical gaze on the role of the artist as author who, in relaying his own observations, essentially creates a fanciful space for sheltering his own “self”.